Kate Welch, Senior Library Assistant.

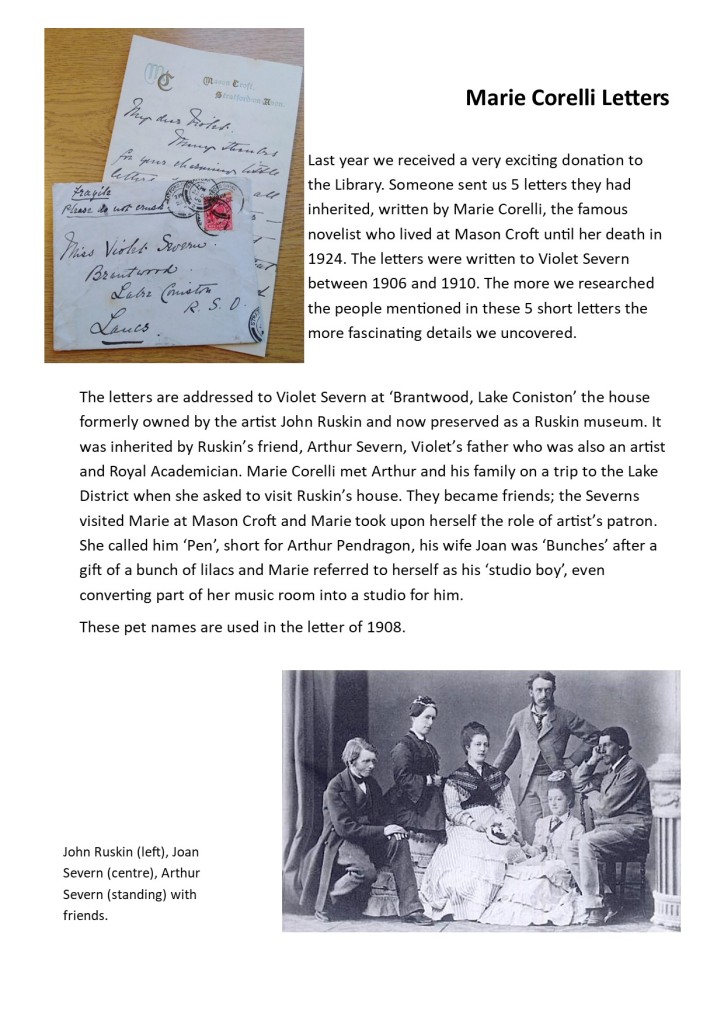

There can be very few still alive who remember anything of the Spanish ‘Flu Epidemic of 1918, though we have plenty of contemporary information and statistics about its origins and spread. First identified in the United States, the virus infected one in three people worldwide and killed 50-100 million, or 2.5 – 3% of a global population of 50 million. It seems a world away. But now, a mere century later, we are in the grip of a new pandemic which has already killed thousands and has radically changed our lives.

Who could have imagined the onset of coronavirus? Unprecedented was the overused word of the moment. But there is nothing unprecedented about the outbreak of deadly disease. In the ancient world, the great city-state of Athens of 5 B.C.E. was a magnet for traders from the Greek and Persian worlds. But where goods went, so did infection and, via the shipping lanes, the plague arrived. Its gruesome physical symptoms were observed by the historian Thucydides. He also noted how the bonds of law, citizenship and custom were disrupted by the disease, plunging the city into anarchy. Athens would never recover its former glory.

In England, the most deadly plague to strike the country appeared around 1348. This was the bubonic plague, or Black Death, so called because of the blackening of skin and tissues as the disease advanced. As in the classical era, it appeared to have been carried from China or Asia, leaving innumerable victims in its wake and ravaging Europe. Here, it was probably brought from Genoa, coming ashore in Dorset. A contemporary writer observed:

‘ (It was) a cruel pestilence hateful to all future ages….it wretchedly killed innumerable people in Dorset, Devon and Somerset….then travelled northwards leaving not a city, a town, a village or even, except rarely, a house, without killing most or all of the people there.’

The writer ruefully notes that the disease was –

‘just as cruel among pagans as Christians .’

Over the years 1347-53, up to 75-200 million people died worldwide. In England the population was halved, declining from 5-6 million in 1300 to 2.75 million in 1377. The plague had catastrophic, long term effects. Population levels took many decades, or longer, to return to normal and enormous economic, social and religious change diverted the course of our history.

Epidemic and pestilence arose in Tudor England during the last 50 years of the 16th century and appeared regularly in the 17th. England had become a maritime power, trading with the New World, Europe and beyond. We can plot the intensively-used sea routes where spices and perfumes were picked up, and where they might be exchanged for luxury consumer items such as furs, silks and gems. The greater the activity of ships, ports and people though, the more likely was the transmission of deadly pathogens. We don’t know what bacterium or virus was responsible for The Sweat of 1551 or how many lives it took, but the death-toll was huge. It was known, ironically, as ‘the scourge without dread,’ owing to its rapid onset: a person in normal health in the morning could be dead by midday. Nevertheless it inspired real terror; one commentator described it as a sickness

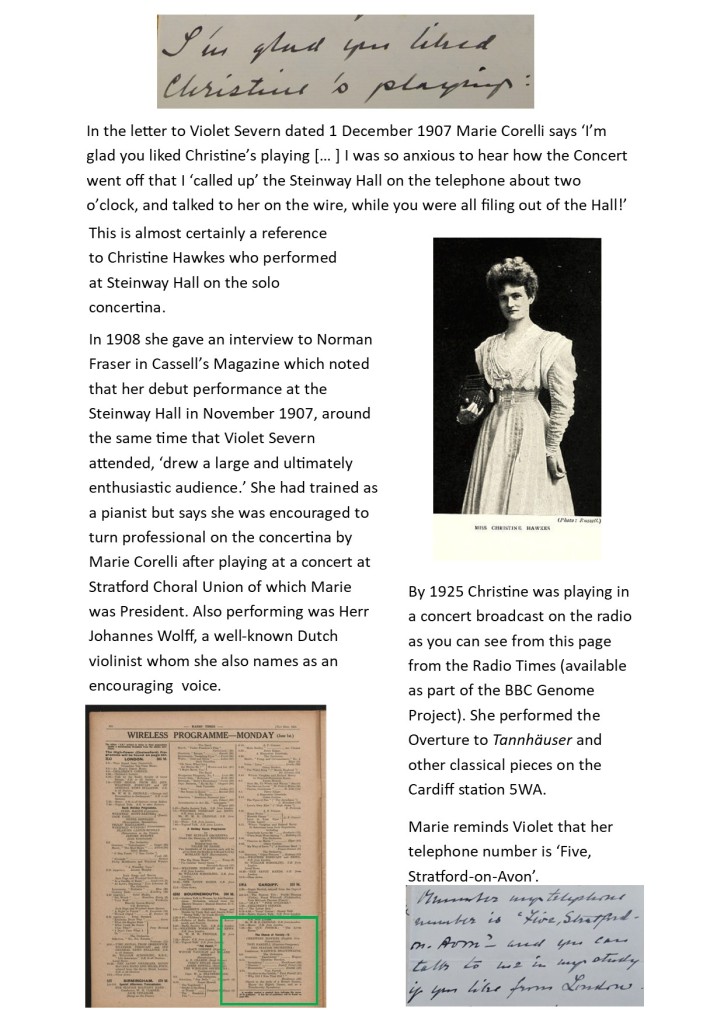

‘so sore, so painfull and sharpe, that the lyke was never harde of….before that time.’

Only seven years later, a strain of influenza appeared, killing one fifth of the population. The theologian Thomas Cooper wrote in his Chronicle:

‘In some shires almost no gentleman scaped but either himself or his wife, or both, were dangerously sick and very many died, so that diverse places were left void of ancient justices and men of worship to govern the country. At this time also died so many priests that a great number of parish churches in diverse places of the realm were unserved.’

Cooper is referring to a whole layer of the Catholic ruling class which was effectively wiped out. Even Reginald Poole, the Archbishop of Canterbury, died only 24 days after ‘Bloody’ Mary, the Tudor Queen who had reinstated hard-line Catholicism in England. It was a dark coincidence and a serious blow for the Catholic church, but a huge gift to the heir to the throne, Elizabeth, who would create a Protestant state as Queen of England. So a microscopic organism again influenced the course of history.

In Stratford-upon-Avon, a certain William Shakespeare was baptised in April 1564. There he is, on the famous, much-reproduced page of the parish register in Holy Trinity Church. But an ominous three words appear in the following July in the same register: Hic incipit pestis. Here begins plague. In the next 6 months just over a tenth of the town, or 237 people, died, four of whom lived on Henley Street: close neighbours of the Shakespeare family. Victims were buried in mass plague pits in Shottery, immediately outside the town, and present day Shakespeare tour buses rumble regularly over the site.

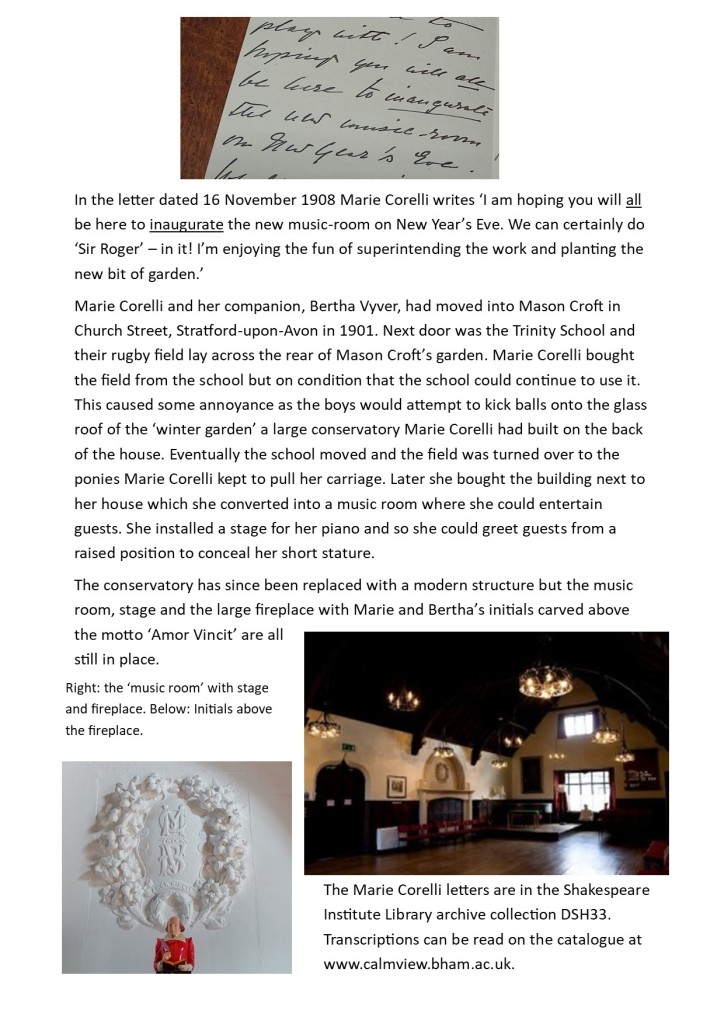

This was not the only outbreak of plague to beset Stratford. The disease lurked, springing up here and there, then seeming to die down again. It was an abiding threat to townsfolk, and the young Shakespeare, growing up, would have heard stories about the 1564 outbreak and kneeled in memory of the lost in church services. His father, John, was involved in relief measures, and records reveal his attendance at a meeting to help Stratford’s poorest. It was held in the open air to reduce the risk of infection, just as we are advised to do during our own pandemic.

In fact, the entire lifetime of Shakespeare – man, professional actor and playwright – was threatened by plague. His son, Hamnet, was a victim at the age of 11, a personal tragedy which might have inspired Hamlet – according to the Shakespeare scholar Stephen Greenblatt, the names were interchangeable at the time. Fellow playwright Ben Jonson also lost a son to plague and afterwards wrote the deeply affecting poem: On my First Sonne, an elegy for a seven year old.

Elizabethan doctors had no idea that the disease was transmitted by rat fleas, but they grasped that social distancing and isolation were necessary measures: as soon as an outbreak flared up, the authorities stepped in to forbid mass gatherings. In the epidemic of 1592-3, the playhouses were first to close: not only did the authorities regard them as hotbeds of immorality and vice, but disease usually struck in the summer months, which coincided with peak season for theatre attendance. Closure had disastrous effects for the industry; many actors died, or were forced into other trades. Companies broke up or had to tour in the provinces, where disease was less concentrated. Plague spelled the end for the Queen’s Men, a successful company which went into the country and never returned. Another company, the Earl of Pembroke’s Men, was also forced to disband, having pawned its props and wardrobe and been obliged to spend the proceeds on basic subsistence.

Life in London was grim. A previous Privy Council Plague Order had created a nationwide set of rules which confined the healthy along with the sick in their own homes. If they did not succumb, people had to live with the decomposing dead. Doors were sealed up and bore red or black crosses. These appalling measures were widely opposed for their inhumanity. On the streets outside, horrific sights and sounds were customary: the rumbling of death carts, cries of “Bring out your dead”, watchmen posted at city gates or outside infected houses, the continual chiming of funeral bells. The appearance of plague doctors was chilling: these wore long robes and sinister beaked masks, the cones of which were stuffed with herbs, in the mistaken hope that infection would be repelled. They carried long sticks with which to examine patients from a ‘safe’ distance. But no-one was safe. There were treatments such as poultices made from roots, herbs and animal fat applied to the dreaded buboes which swelled in the throat, armpits and groin. Cordials of hops, rue and other plants might be given, the whole body rubbed with snake or pigeon flesh, a dead toad bandaged to the abdomen. Draughts of vinegar, mercury, arsenic or powdered minerals were prescribed which did more harm than good. Cinnamon was thought to bring down high fever, dried rhubarb to drive contagion out. But none of it worked. What was needed was the antibiotic which usually cures those cases of plague (yersinia pestis) which still arise in modern day Asia and China.

In 1592, Shakespeare had only recently arrived in London but had already attracted notice with his Henry VI plays. Where was he when the playhouses closed? Probably he took refuge with his family in Stratford, or if he remained in London, he must have isolated himself to avoid infection. Denied the playhouse, he earned money by composing the two great narrative poems: Venus and Adonis in 1593 and The Rape of Lucrece, a ‘graver labour’, a year later. When the plague abated he resumed his playwriting career, probably writing Romeo and Juliet around that time. ‘A plague on both your houses’ cries the fatally wounded Mercutio. Later in the play, plague is used as a plot device when Friar John is sealed up in an infected house, fails to deliver the crucial message, and so brings about the tragic deaths of the lovers.

Another outbreak of plague hit London in 1603, causing more than 33,000 deaths. Theatre was by then the pre-eminent leisure industry in the city and the focus of huge economic activity. There were more than half a dozen playhouses on Bankside and an estimated 20,000 theatre visits each week. Entry was cheap and up to 3000 people at a time could be accommodated. This time, the closure of the playhouse lasted for 14 months and actors suffered worse privations than they had during the 1592 outbreak. Again they were obliged to support themselves as best they might. The new King, James 1, however, bestowed a gift on Richard Burbage, the great actor of Shakespeare’s company: the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. The order came from Court in 1604, granting the sum of £30 –

‘by way of his Majesty’s free gift… to Richard Burbage… one of His Majesty’s Comedians… for the maintenance and relief of himself and the rest of his Company… being prohibited to present any plays….by reason of great peril’

A foreshadowing of Rishi Sunak’s Arts Rescue Package perhaps? Soon after, James’ Court issued a proclamation by which Shakespeare’s Company became The King’s Men. It –

‘licensed and authorised….these Our servants….freely to use and exercise the art and faculty of playing Comedies, Tragedies, Histories, Interludes, Morals, Pastorals, Stage-plays… as well for the recreation of Our loving subjects as for Our recreation and pleasure.’

The fortunes of the King’s Men were assured – except that they still had plague to contend with. After months of inactivity, theatre companies began cautiously to open in their own houses and to return to their repertoire. But restrictions still existed: they were only permitted to remain open –

‘ except there shall happen weekly to die of plague above the number of thirty within the City of London and the liberties thereof, by which time we think it fit they shall cease and forbear any further publicly to play until the sickness be again decreased to the said number.’

The authorities were wise: plague returned yet again in 1606. It was less severe than the 1603 outbreak but continued to spring up sporadically during the next few years. The playhouses opened, closed and re-opened. In fact, between 1603 and 1613, they were closed for an astonishing 78 months: more than 60% of the time. The vitality of the new genre carried it through, though plague changed its evolution. It would, as a living art-form, have changed anyway, but in 1604, defiant against all the odds, a new house opened: the Red Bull Theatre. This offered plays which provided rousing spectacles and had a nationalistic feel-good flavour. It appealed to the lower end of the market and audiences came, in the knowledge that a certain risk was attached to theatre-going – but came anyway. Shakespeare’s King’s Men, as they picked up the pieces after closure, went in a different direction. They now began to move up-market towards establishing a new indoor house, the Blackfriars Theatre. This would extend the season and would allow them to recoup the money lost from closures, whilst attracting more elite audiences who were willing to pay higher prices.

As for Shakespeare, some theatre historians suggest that he wrote King Lear during that 14 months’ lockdown, over 1603 – 4. He might have done so, for the play had its very first performance before the King in 1606, and was probably scripted that year, or the year before. It is noticeable that in the plays written after the outbreak of 1603, disease references appear regularly in Shakespeare’s work. In Lear itself, the servant Oswald is cursed with: ‘A plague upon your epileptic visage.’ Lear himself speaks of the ‘plagues that hang in this pendulous air,’ referencing the common theory that airborne transmission spread the disease. He even compares his daughter Goneril to the dreaded plague buboes, calling her ‘a sore, an embossed carbuncle.’ Lear may be Shakespeare’s bleakest play; it is saturated with death, despair and chaos, as London must have been at that time. In Timon of Athens, speeches are similarly full of references to plague: ‘Your potent and infectious fevers heap/On Athens!’, ‘send them back the plague/ Could I but catch it for them.’ And in Macbeth there are numerous references to the corrupt and ‘filthy’ air which was thought to engender plague, and the ‘infected’ air upon which the three witches ride.

In our own times, we have recently emerged from a period of lockdown. We understand now what it is to be ‘cabin’d, cribb’d, confined, bound in,’ fearful of infection. Our theatres are dark, coronavirus is still very present and the threat of unemployment and economic hardship grows closer. At a stroke, we are suddenly closer to Shakespeare‘s world of dread and life-changing, virulent sickness. We are reminded how greatly the new playwriting industry of the 1590s and 1600s was afflicted by bubonic plague and how it changed Shakespeare’s creative life and output.

Some scholars suggest that Shakespeare might have written more plays, had continual outbreaks of plague not intervened and left us the poorer. But others believe that the presence of plague acted as a spur to his imagination during the years when his genius was in fullest flower. For evidence, we have only to look at what he created during those uncertain times.

Bettina Harris, Library Assistant

We couldn’t run the library without them! This week, Fran Clarke describes what it’s like to be a Casual member of staff in our library.

Our pool of Casual Staff at the Shakespeare Institute Library provide invaluable cover; keeping the library running with professionalism and great customer service. Mainly, they ensure that our contracted staff can go on holiday, be sick or attend meetings whilst leaving the library in good reliable hands. Fran Clarke has been with the SIL for four years and is a valued member of the team. Like all our Casual staff we benefit from the knowledge, experience and skills she brings with her. Coming from all walks of life, our Casuals bring different perspectives and ideas. However, they all have something in common – they are wonderful team members and an incredible asset to the SIL.

——————————————

I will never read a newspaper the same way again. One of the main ongoing tasks for a casual at the library is to work on the newscuttings archive. If it relates to Shakespeare it’s in. I really relish being a Shakespeare detective checking the papers for articles with any mention of him, the RSC, Renaissance drama, relevant theatre productions, the historical period and obituaries of actors who have appeared in Shakespeare. Also quotations and their adaptations, it seems the newspapers cannot resist a Shakespeare pun. It’s scissors at the ready at the sight of an article featuring Dame Judi Dench! I really enjoy the whole process of the archive and I am pleased to be involved in contributing to this resource.

There are of the course the usual tasks involved in working in the library such as: issuing and discharging books and assisting students find books and other material. Casuals also help with shelf checking to ensure the books are where they should be.

The SI library has a friendly calm atmosphere, set in a lovely oasis of a garden in the middle of the town. It is very welcoming to students and is a great place for peaceful study. As casual I have had the pleasure of working with all the members of the library staff and no shift is ever the same but it is always quiet.

Frances Clarke, SIL Casual

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments.

Although, quite often, impediments arise, as we all know. Maybe our heart of hearts and ray of sunshine leaves the toilet seat up, or badgers us endlessly about toilet seats for some reason. Maybe they appear to have developed a particular deafness to our exasperated sighs, or a peculiar blindness to our frowns. While we know, as in the sonnet, we should not admit impediments to the marriage of true minds, yet quite often the other person becomes expert at delivering a very slow, yet very persistent kind of grinding, that could reduce even the most patient saint to fine, and entirely angry, powder.

Maybe, we consider as V-day looms on the horizon, the true minds Shakespeare mentions are not actually a description of love between two people. Maybe, and I think, far more likely, the deep and unswerving belonging at the heart of the poem is meant to paint an image of reader and book. I admit singledom may have something to do with my reading, but hear me out. While books have in the past disappointed, it was never through inconsideration. While some of them are fragile, none of them will ever demand hours of cuddles when you are not in the mood. While most of them end, you can see that one coming from a mile off, indeed, you can measure the time to the inevitable. Book can be heart-achingly beautiful, mind-bendingly clever, and knee-bucklingly charming, all at once.

So this valentine’s I’m picking up my date from the SIL, taking my time to peel off the outer layers, before going for a leisurely walk about town, and finally to bed and to the marriage of true minds. I will, in other words, be picking up one of our marvellous blind date books, and let the words rock my world. I recommend you do the same. You could even bring your own date.

Dr. Sara Marie Westh, Library Assistant

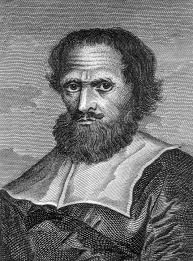

A great man of the Elizabethan theatre died in the second decade of the 17th century. He was the A-list superstar of his age, intimately connected to many of the playhouses in London’s new Theatre-Land, but the Globe in particular. His fans adored him and he was described as ‘their mortal god on earth’ and a man ‘not to be matched.’ The public outpouring of grief at his passing was so great that it almost eclipsed the regulation mourning for Anne, the Queen consort of James I, who had recently died. Both city and theatre, the common and the great, felt his loss: the Earl of Pembroke wrote that he could not bear an evening at the playhouse – ‘being tender-harted …so soone after the loss of my old acquaintance’ – while a sincere, if somewhat lacklustre poet lamented: ‘He’s gone and with him what a world are dead.’

This was not Shakespeare. We imagine, perhaps, that it should have been. But, though this man was praised and mourned in his own time, he seems to be half-forgotten and almost to have been air-brushed out of history. There exists only one biography of him, written in 1913, whereas the life and work of Shakespeare have been minutely examined and speculated upon. No theatre is named after him or displays his name. Yet he was Shakespeare’s friend and closest colleague who had been a member of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men from 1594, remaining with the Company through its transition into the King’s Men in 1603, and beyond.

Our man is considered to be the first great actor of the English stage. His name is listed second to Shakespeare’s In the First Folio of 1623. And for him, Shakespeare wrote leading roles in at least a third of the canon from Lear, Othello and Richard III to Coriolanus, Romeo and Hamlet. He was in his time the greatest actor anyone had seen; testimony is unanimous in saluting his remarkable talents.

He was described as having a ‘wondrous tongue’ and for John Gee, writing in 1624, he was: ’the flower and the life of his company, the Loadstone of the Auditory, and the Roscius of the stage.’

Otherwise he was regarded as ‘the best Tragedian ever played’ while a long funeral ode refers to the various Shakespearean characters he had made so memorable who had ‘died with him…. never to revive’ – a loss so great that ‘tragic night/ Will wrap our black-hung stage.’ A later poem imagines how the audience at the playhouse:

‘Thrilled through all changes of Despair,

Hope, Anger, Fear, Delight and Doubt

When Burbage played.

For Richard Burbage it was (who else?} who inspired such adulation.

Who was Burbage? How did his rise to greatness come about? Unlike many another great artist, he did not apparently spring out of nowhere, or from humble origins. The theatre was in his genes and in his blood, for he was born into a family dynasty which dominated theatrical management and enterprise in London for over 70 years.

His father James, was born around 1531, probably in Warwickshire. A carpenter by trade, he left the safe, beaten track of his profession and re-emerged as the chief of the actors nominally attached to Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. This was a tenuous position, for players lacked the status of ‘servant’ which would have granted then greater job security. As players were obliged to move from place to place, they were generally classed with the raggle-taggle of rogues and vagabonds who thronged the roads. It is James Burbage who is the leading signatory in a letter to Leicester, begging that he and his colleagues should be recognised as bona fide servants of their Lord. In response, Leicester obtained the first Royal Patent ever granted to a group of actors, elevating them to the status of artists. In a bold stroke of innovation, James Burbage, realised that a permanent theatre in the capital itself would bring in more money and act as a stable, permanent base. Having rented a site in Shoreditch he built The Theatre in 1576. In construction and name, it referred to the Roman amphitheatres of antiquity and it was the first ever playhouse in this country.

James Burbage and his two sons, Cuthbert and Richard, born in 1565 and 1568 respectively, receive frequent mention in histories of the stage. Cuthbert, the elder brother, was never an actor but managed the family enterprise. He owned the ground lease of The Theatre, played a major role in the construction of the Globe, and, by the cultivation of wealthy patrons, contributed to the Burbage’s success and longevity – and to the career of Shakespeare. Women were equally important in the business, particularly James’ wife Ellen, and Richard’s wife Winifred. The latter retained shares in the Burbage properties until 1643 when Parliament closed the theatres.

It was into this larger family of colleagues and collaborators that Shakespeare entered in the early 1590s. He had already shown his versatility in plays in a variety of genres: Two Gentlemen of Verona, Henry VI, Richard III and Titus Andronicus. He had also gained the Earl of Southampton as both friend and patron, and this gave him an entrée to a world of literary and intellectual patronage. He was probably a founder member of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, along with his colleague, Richard Burbage, amongst others.

Richard was well known as a gifted actor early in his career: as a young boy, he had almost certainly played female roles in his father’s theatre. He had taken the role of Old Knowell in Ben Jonson’s Every Man in his Humour, had been one of the duo of conmen in The Alchemist, and Duke Brachiano in Webster’s White Devil. He was in demand by a number of other Elizabethan playwrights too, and, by his early twenties, was playing Richard III. Already he was a sensation, and never more so than when he was playing Shakespeare. One of the odes in his honour recalls:

‘ Oft have I seen him leape into a grave

Suiting ye person (which he seemed to have)

Of a sad lover, with so true an eye

That then I would have sworn he meant to die’

The Ode continues:

‘What a wide world was in that little space,

Thyself a world, the Globe thy fittest place!

Thy stature small, but every thought and mood

Might thoroughly from thy face be understood,

And his whole action he could change with ease

From ancient Lear to youthful Pericles.’

And the apothecary, Simon Forman, a regular theatre-goer, records a striking piece of acting when the entrance of Banquo’s ghost in the banqueting scene, throws Macbeth (Burbage) into ‘a great passion of fear and fury.’

Clearly, Burbage was a compelling performer, able to move seamlessly from one role to the next. ‘He was a delightful Proteus,’ wrote a contemporary, ‘so wholly transforming himself into his part and putting off himself with his clothes, as he never…assumed himself again until the play was done.’ He was praised, too, for his expressive hand gestures and his ability to stride, pace or stalk, as his role demanded. It was even said that he could blench or blush at will, and that, when at the height of a passionate speech, buttons would fly off his coat. These, though exaggerations, attest to his emotional power and huge presence on stage.

‘He [Burbage] must have been extraordinary’ comments the actor Simon Russell Beale, who has acted nearly every Burbage role in the book. Russell Beale is struck by the psychological intensity of the roles played by Burbage: Lear falling into madness, the jealousy-crazed Othello, the murderous psychopath Richard III. Above all, it is Hamlet which requires a large range of emotions – anger, grief, sarcasm, desperation. ‘[Burbage] must have been extremely good at expressing those extremes of behaviour in a sympathetic way…a watchable way’ Russell Beale concludes.

Burbage also had responsibility for the running and upkeep of The Theatre and for the supplementary Blackfriars Theatre, set up by his father. In the glory days at the Globe, he and his fellow actors would have had to memorise up to 800 lines for each play in a repertory which presented up to 15 plays a month. Dynamic, hugely vigorous and energetic he must have been.

In 1597, James Burbage died, just before the lease on The Theatre expired. The Lord Chamberlains Men were in trouble. An extension on the lease had not been negotiated, though luckily there was a clause in the original agreement stating that while one Giles Allen owned the land, James Burbage owned the theatre he built on it. While Allen was away at his country home in Essex, around Christmas 1598, Richard with a dozen or so supporters and workmen, began the task of demolishing The Theatre with the intention of re-erecting it, phoenix-like, on a pre-selected site on Bankside, over the river. The aggrieved Allen afterwards testified that the Burbage faction armed with ‘swords, daggers, bills [and] axes….forcibly and riotously….in a very outrageous, violent and riotous sort’ began pulling down the theatre. Their appearance naturally drew a crowd – friends and tenants of the absent Allen, as well as supporters of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, including James Burbage’s feisty widow, Ellen. And presumably those whose livelihood was at stake, such as William Shakespeare, were present too.

The whole undertaking was described as being a ‘great disturbance’ and ‘terrifying…to [the Queen’s] loving subjects there near inhabiting.’ Nevertheless, during the next few days, the cannibalised timbers were carted across London Bridge and erected on new foundations to form the Globe theatre. The great days of the Globe were at hand.

History was made in the Globe over the next fourteen years. Shakespeare wrote his most famous plays for it and on its boards Burbage gave the first performances of Hamlet, Othello, King Lear and Coriolanus, amongst others. What was the relationship between playwright and performer? How did they work together?

An anecdote written down in 1602 by John Manningham, a law student, recounts how a woman in the audience developed a violent crush on Burbage during his performance of Richard III. An assignation was arranged, which was overheard by Shakespeare. When Burbage turned up for the tryst, sending word that Richard III was at the door, he found that Shakespeare had arrived earlier. A message was returned stating that William the Conqueror was before Richard III. Another amusing speculation concerns the Act V sword fight in Hamlet where Gertrude comments that her son is ‘fat and short of breath.’ Was this a sly jibe at Burbage’s increasing weight?

Shakespeare was no solitary genius. He wrote the plays in intimate collaboration with a resident team of players, most of whom he knew throughout his whole working life. He was completely familiar with Burbage’s capabilities – his voice, technique, and that emotional intensity which allowed the playwright to go deeper into the psychology of his characters, knowing that here was an actor who could interpret all their nuances. We feel intuitively that Burbage was Shakespeare’s muse, an equal and committed co-creator of the plays and roles. The dramatic inspiration ran both ways.

Practising actors understand that in a named play – such as Macbeth – the character with the most lines almost becomes the director. He needs the other actors to conform to his vision, and may stretch and pull in various directions, the author who is writing for him. How much input was Burbage allowed? Did Shakespeare re-arrange a scene at the urging of his most charismatic actor? Might one have said to the other, ‘Er – can we take a different approach here? Was Shakespeare reluctantly forced to change a word, a line or (God forbid!) a whole speech? As anyone who has ever sat in a rehearsal room must know, playwrights seldom have the last word. Whatever the facts, the collaboration of playwright and actor was to change the world.

Members of the Burbage family are buried in St. Leonards, Shoreditch, though their tombs are now lost. The story goes that Burbage’s stone bore only two words: ‘Exit Burbage.’ There is, however, a memorial plaque on the wall, containing a long list of theatre people buried in the church. Burbage is simply described as ‘the first actor to play the parts of Richard III and Hamlet,’ Otherwise, he is elusive, except for a painting in Dulwich Art Gallery. Long tradition claims that it is his portrait; a newer idea suggests it is a self-portrait, for he was said to be a skilled artist. Art historians, however, will not commit themselves either way.

The picture shows a plain, sober, even melancholy man. There is no sense of the theatrical or any real sign of the charismatic presence which Burbage demonstrated on-stage. For a man of such oratory, the mouth is small and insignificant though the gaze is direct, even compelling. We have no clue as to the context of the painting; if it is indeed Burbage, it may simply be a private image for family alone, and one unconcerned with showing off fame or status.

On March 13, 2019, residents of Burbage Road, Dulwich marked the 400th anniversary of Burbage’s death with a walk setting off from his resting place in St. Leonard’s Church, Shoreditch. Their journey commemorated his decision to remove The Theatre to Bankside, rebuilding it as the Globe theatre. ‘This has given us the opportunity to bring the message to those in Southwark, home of great Shakespearean theatre,’ said an organiser. A mural, celebrating Burbage, was unveiled on Burbage Road. It is sited on a railway arch and places him centre stage, surrounded by quotations from the plays he helped make famous.

When Shakespeare died in 1616, he left money to three colleagues to buy mourning rings in his memory. Two of these were Henry Condell and John Heminge, who eventually brought about the publication of the First Folio of the plays. And the third was Richard Burbage.

Bettina Harris, Library Support Assistant

We are used, in this media-dominated age, to encountering fictional representations of the great figures of our culture. It is more the case with Shakespeare, than with any other individual, and is conveyed in every conceivable art form. He is a global icon, immediately recognisable, usually portrayed with that mask-like face and high forehead which has become less than human, and more and more a brand image, as ubiquitous as the Coca Cola logo.

Shakespeare’s appearances as a character are far from fixed or static: he has lived many fictional lives which have been portrayed through a vast variety of approaches. We know so little about his private life that to present him as a character allows any amount of solutions to the identities of, for instance, the Dark Lady or Mr.W.H.. We may be offered insights into his relationships with Sir Thomas Lucy or Christopher Marlowe. His marriage may be given a melodramatic soap-opera spin, where William appears as a serial adulterer, Anne as a faithful but unappreciated wife. Or the other way round. These can seem serious or be ridiculous: the great playwright walking his chihuahua, a depressive on Lithium, or an addict mainlining cannabis.

Though fictional Shakespeares take many liberties with the known facts – and there are precious few of those – unverifiable myths such as the Deer Poaching episode stand side by side with the scholarship that is continually careful to discredit them. There is a ‘kinship of interest’ as one critic comments, ’like theologians fascinated by sin,’ which holds the unlikeliest fictions featuring Shakespeare in affectionate regard. Besides that, the genre of fictional lives has a mass appeal, and whereas scholarship attracts a smaller elite, our television series, films, dramas and prose narratives appeal to large audiences. And for many, there is the yearning for direct contact; ‘I began with the desire to speak with the dead’ wrote Stephen Greenblatt, of his biography of Shakespeare. How many of us, Shakespeare critics or not, have dreamed of what they would ask the Bard? I have quite a list of questions myself.

Literary fantasies, underlying the desire for direct communication, began to appear  before 1800 and usually present the Bard as a ghost. But, actually, Shakespeare had long pre-empted these manifestations in his own lifetime, by appearing in person, as an actor in his own play. Or so says Nicholas Rowe in his biographical account of 1709. Cosy, gossipy, but unfortunately unable to verify the various orally-transmitted stories he had gathered together around Stratford, Rowe writes that he ‘could never meet with any further Account of him…than that the top of his Performance was the Ghost in his own Hamlet’

before 1800 and usually present the Bard as a ghost. But, actually, Shakespeare had long pre-empted these manifestations in his own lifetime, by appearing in person, as an actor in his own play. Or so says Nicholas Rowe in his biographical account of 1709. Cosy, gossipy, but unfortunately unable to verify the various orally-transmitted stories he had gathered together around Stratford, Rowe writes that he ‘could never meet with any further Account of him…than that the top of his Performance was the Ghost in his own Hamlet’

This traditional story from Rowe, marks the emergence of Shakespeare as ghost figure. Like the spectre of Old Hamlet, he is a figure of authority and moral integrity, coming not kindly, but to castigate posterity and set right corruption. So, in John Dryden’s 1679 adaptation of Troilus and Cressida, the ghost of Shakespeare arises to berate the current degenerate state of the theatre:

‘Now, Where are the Successours to my name?

What bring they to fill out a Poet’s fame?

Weak, short-liv’d issues of a feeble Age;

Scarce living to be Christen’d on the Stage’

Rather more mundanely, the ghost of Shakespeare was useful in theatrical disputes: in an adaptation of Measure for Measure in 1800, he appears to speak an epilogue which praises the production and castigates a rival company ‘on yonder stage.’ The audience would, of course, have known exactly who that was. But this sort of treatment had the effect of diluting the authority of the Shakespeare figure, which is some quarters, became an outright object of mockery. In Farquar’s The Constant Couple, the prologue ridicules the ghost for trying to ‘fright the ladies,’ warning that it was ‘the DEVIL did Raise that Ghost’ and remarking:

‘Let Shakespear then lye still, Ghosts do no good:

The Fair are Better Pleas’d with Flesh and Blood’

The ghost also turns his attention to political matters where he assumes a manner of grim seriousness, particularly where the French are concerned. In a poem by Mark Akenside, the spectre rouses the nation against the French, while an anonymous tirade of 1803 sees Shakespeare:

‘in the character of A TRUE ENGLISHMEN and A STURDY JOHN BULL,

Indignant that A FRENCH ARMY should WAGE WAR IN OUR ISLE’

Though, up to the present day, some Shakespearean ghosts are still regarded as figures of literary and moral authority, they are more usually raised for the purpose of ridicule. A satirical sequel to Hamlet was written in 1901, in which the new ruler, Horatio, builds a wing to his palace in order to escape the many ghostly casualties of the play. A new, arrogant ghost arrives, wanting to move in: Shakespeare himself. Horatio is obliged to call up his solicitor and have the spirit ejected.

A comic verse, not likely to amuse Bardolators – appeared in the 1920s:

I dreamt last night that Shakespeare’s ghost

Sat for a Civil Service post:

The English paper for the year

Had several questions on King Lear

Which Shakespeare answered very badly

And in 2007, the Shakespearean actor Mark Rylance produced a play called I Am Shakespeare in which the magic of the Web raises the ghost of the Bard. He is forced to defend his authorship by a troupe of other ghosts, who claim to have written his works. Reviewers at the time noted how unusual it was for an actor to suggest that someone other than Shakespeare wrote the plays attributed to him. But Rylance is an ‘Anti-Stratfordian’ and really let rip in this production. After a thorough mauling from the ghosts – and even from a passing cop who applies Jack the Ripper identification techniques to the authorship question – Shakespeare is reduced to tears of self-pity in the final scene and is diminished both as a man and a dramatist.

And in 2007, the Shakespearean actor Mark Rylance produced a play called I Am Shakespeare in which the magic of the Web raises the ghost of the Bard. He is forced to defend his authorship by a troupe of other ghosts, who claim to have written his works. Reviewers at the time noted how unusual it was for an actor to suggest that someone other than Shakespeare wrote the plays attributed to him. But Rylance is an ‘Anti-Stratfordian’ and really let rip in this production. After a thorough mauling from the ghosts – and even from a passing cop who applies Jack the Ripper identification techniques to the authorship question – Shakespeare is reduced to tears of self-pity in the final scene and is diminished both as a man and a dramatist.

The presence of an electronic device in Rylance’s play is indicative of how science fiction has offered an alternative way of gaining direct contact with Shakespeare. A time machine, or similar device, either transports a character to the 16th century to meet the playwright in his own age and setting, or else transports Shakespeare to the present era. Time travel fantasies are usually associated with popular culture and the TV series Doctor Who presented a memorable episode called The Shakespeare Code in 2007. This saw the doctor and his companion arrive at the Globe theatre in 1599 and become involved in a plot where evil aliens pose as three witches. The episode fuses the magic and witchcraft of Shakespeare’s writing with the Doctor’s pseudo technology, so offering perspectives on traditional views of Shakespeare’s age and plays, and the imaginary future world of scientific advances.

A paternal Shakespeare appears in Susan Cooper’s 1999 children’s novel, King of Shadows. Nat Fields, an orphaned young actor, is transported to Renaissance London where he plays Puck to Shakespeare’s Oberon: a father/son pairing. He defeats the traumas of adolescence and the grief of losing his parents through contact with the father-figure of Shakespeare, who represents support and love, as well as cultural authority. In many of these books for children, a solitary protagonist travels to London and becomes involved in theatre. Shakespeare is usually presented as an idealised mentor, offering parental-style support and encouragement and guiding the youngster into a successful adulthood.

Another strain of fiction focuses on Shakespeare’s life in the theatre: the problems surrounding stage productions, his style as actor-manager, or his relationships with colleagues and rival playwrights. In contrast to the children’s genre, Maurice Baring’s The Rehearsal is bitingly satirical with Richard Burbage, The Globe’s prime actor, ripping apart (not literally) the ‘tomorrow, tomorrow, and tomorrow’ speech in Macbeth. ‘It’s a third too short’ rages Burbage, ‘There’s not a single rhyme in it …. it’s an insult to the stage. “Struts and frets” indeed!’

It is impossible not to mention Neil Gaiman’s Shakespeare stories for the Sandman comic book series. Shakespeare appears discussing his work with Marlowe and tellingly refers to Dr Faustus: ‘I would give anything to have your gifts, or more than anything to give men dreams…that would live on long after I am dead.’ His wish is granted by Lord Morpheus, a supernatural being from the domain of dreams and myths.

Shakespeare has lived in many fictional lives: philanderer, faithful husband, gay, bisexual, straight, black, white, male, female, amongst others. Even a brief glimpse into these apparitions charts the preoccupations of a particular author, age or nation, and pinpoints the ideological, social, religious or political concerns which underlie them. In the present age of technological advances, the range of media is so extensive that Shakespeare as a fictional being can appear anywhere and in almost any form. He is the mirror of a period, an outlook on life and a ghost that refuses to lie down.

Bettina Harris, Library Assistant

“It’s a part in which you can’t fail, and you can’t succeed because it’s not about finding answers. It’s all about asking questions.”

The Shakespeare Institute Library is extremely fortunate to have amongst its actors’ script archive Samuel West’s scripts. His collection covers his work as both actor and director of Shakespeare and other work. It is wonderful to be able to promote the research possibilities of this script collection. This exhibition features just some of Samuel’s treasured material.

Photo by Nils Jorgensen

Samuel West was born in London on June 19, 1966, the son of the actors Prunella Scales and Timothy West. It was perhaps inevitable that he would follow them on to the stage, since both his parents have had successful acting careers and even his grandparents Lockwood West and Olive Carleton-Crowe were also actors.

Though Sam West claims that he and his parents do not constitute a ‘family firm’ of actors, the three have appeared together on several occasions. West’s portrayal of Prince Hal in 1996 was opposite his father, Timothy, as Falstaff; they played the same character at different ages in the film Iris, and all the family took part in a reading of Pinter’s play Family Voices. He records that when he told his parents that he wanted to be an actor, they replied ‘Be a plumber.’

West ignored the advice and went on to win a number of awards, act and direct in every medium, and is now one of our most highly regarded Shakespearean actors.

He made his London stage debut in 1989 playing Michael in Cocteau’s Les Parents Terribles which drew positive critical comment. Early Shakespearean roles included Prince Hal for the English Touring Theatre’s production of both parts of Henry IV, and Octavius Caesar in Antony and Cleopatra at the National Theatre.

Photo by Malcolm Davies

In the first of his two seasons with the RSC he undertook the title role in Richard II in Steven Pimlott’s production of 2000. West’s account of planning the production describes how the company saw the play as a chronicle but also a fable, not so much about a king holding on to power as an individual trying to come to terms with mortality. The play was designed with minimal set and props, blue and white lighting that contrasted with darkness, and costumes which evoked the shadows cast on the set.

West has written about the “ammo box” which began life as the base of his throne, became the mirror Richard “crack’d in a hundred shivers” and finally ended as Richard’s coffin.

Reviews were enthusiastic; “A Richard to remember” wrote the critic Dominic Cavendish. In a bold stroke, the soliloquy at Pomfret – “I have been studying how I may compare/ This prison where I live unto the world”- was repeated by Richard’s rival and his queen: the king’s loss of identity a universal condition, not an individual insight. The rehearsal discussions had clearly born fruit.

In 2001, again directed by Pimlott, West played Hamlet. He appeared at first as the typical young student, dressed in jeans and leather jacket, but was soon revealed as clever, able to see through other people’s rhetoric, yet aware of his own powerlessness. West’s performance was set in a highly political world where individual conscience is stifled by power without morality and was generally described as “brilliant.”

Whilst working on Hamlet, West produced three notebooks and one very heavily annotated script. The notebooks cover his initial thoughts and ‘homework’ on the play; his rehearsal process; and fine-tuning of his performance in previews. Evidently a cerebral actor, West’s rehearsal notebook goes into great detail on Hamlet’s relationships with other characters as well as discussing major themes in the play. His ‘reading list’ includes sources as diverse as The Spanish Tragedy, Festen, Fight Club and Batman.

Whilst working on Hamlet, West produced three notebooks and one very heavily annotated script. The notebooks cover his initial thoughts and ‘homework’ on the play; his rehearsal process; and fine-tuning of his performance in previews. Evidently a cerebral actor, West’s rehearsal notebook goes into great detail on Hamlet’s relationships with other characters as well as discussing major themes in the play. His ‘reading list’ includes sources as diverse as The Spanish Tragedy, Festen, Fight Club and Batman.

The production featured many memorable bits of staging which are not referred to in the original script, for example in the Ghost scene the phantom held his son close to him in their shared distress, and before Hamlet is sent to England he kissed Claudius squarely on the lips.

Combined with the notebooks, West’s script is a revelation as to how this actor deciphered one of Shakespeare’s most challenging roles.

From 2005–7 West was artistic director of Sheffield Crucible Theatre. As a passionately political man with strong left-wing beliefs, he believed that theatre was a strong vehicle for airing vital issues and making people think. Accordingly, he revived and directed the controversial The Romans in Britain and also directed As You Like It.

West’s As You Like It, which was also performed on the Swan stage in Stratford in 2007, played with ideas of the fluidity of identity with a collection of hats sprouting from the stage to be tried on by the company. The cast included Eve Best, Lisa Dillon and Sam Troughton. Reviews praised Best for “showing all the symptoms of a sparkling wit with a gnawing need inside” and for her “radiant emotional intelligence”.

Eve Best in As You Like It, Sheffield Crucible, 2007

Starting the play with ‘All the world’s a stage’ as a framing device was “subtly magical” but while Michael Billington called it “an eye-opening As You Like It” others thought it “laboured” and “too earnest” and Charles Spencer thought the approach “a load of old bollocks”.

There was praise for West’s leadership of the Sheffield Theatres – both for his choice of plays and his ability to attract actors to the venue and this, his farewell production, “makes one wish he were staying longer.”

West has also appeared in a variety of films including Notting Hill, Hyde Park on Hudson and Darkest Hour but was in the role of Leonard Bast in E.M. Forster’s Howards End in 1991 that he made his name. Bast signals the arrival of the urban white-collar worker in British society, a role that could have been tailor-made for the politically aware West. He plays him as a tragic hero whose dreams of a higher form of existence are in contrast to the spiritual inertia of an office job. He received a nomination for the role at the 1993 BAFTA Film Awards. West was also cast as the colourless and emotionally sterile St. John Rivers in Zeffirelli’s 1996 Jane Eyre, and was praised for his portrayal of the character in an otherwise not highly rated production.

On television, West has had leading roles including Anthony Blunt in Cambridge Spies, a BBC drama about Kim Philby and his associates. In ITV’s 2011 Eternal Law he played Zak Gist, one of two angels who have fallen to earth in order to serve Humankind. The mix of fantasy and legal satire appeared initially to be an intriguing and promising, but critics found it too absurd to take seriously, particularly when West and his colleague appeared with huge white wings sprouting from their backs. Appearances in long-running series, such as Midsomer Murders, Poirot, Mr Selfridge and Grantchester, made West a familiar face on-screen and his prolific work on radio and as a voice artist for audiobooks and documentary narrations make his an instantly recognizable voice.

He is a long-time collaborator with the Shakespeare Institute and has a personal connection to the place. One of West’s earliest Shakespearean roles was Florizel in a 1985 Oxford Playhouse production of The Winter’s Tale in which Michael Dobson, our current Director, played Time ( …and claims to have upstaged him).

In 2016, as part of the birthday celebrations also marking 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, Samuel West, as Garrick, narrated the actor-manager-playwright’s 1769 Jubilee Ode at Holy Trinity Church giving it its first full-scale performance since the eighteenth century.

In 2016, as part of the birthday celebrations also marking 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, Samuel West, as Garrick, narrated the actor-manager-playwright’s 1769 Jubilee Ode at Holy Trinity Church giving it its first full-scale performance since the eighteenth century.

Samuel West generously donated his script collection to the Shakespeare Institute Library in 2012 and our students have already mined the scripts for course work, theses and dissertations. 2014 saw West receive an honorary Doctorate of Letters from the University of Birmingham.

Sarah Werner, Studying Early Printed Books (1450-1800): A Practical Guide (Wiley Blackwell, 2019)

Sarah Werner, Studying Early Printed Books (1450-1800): A Practical Guide (Wiley Blackwell, 2019)

There can be few students of Shakespeare and the early modern period who do not come into contact with early printed books at some time or another during their studies – and some, of course, more frequently than others. But while we may become familiar with their format, there are always questions at the back of our minds: How were these books printed? Why were they printed in the way that they were? Who was involved in their production? What is the meaning of the printers ornaments, headpieces and tailpieces? How were the pages identified? What were the costs involved? Why is the spelling inconsistent? And why might two copies of the same book bought from the same bookseller at the same time be different from each other?

In this excellent book – a practical guide – Sarah Werner addresses all these questions and more in a detailed account of the entire printing process of the early modern book, from blank sheets of paper to sequential pages of printed text (it was the responsibility of the bookseller, not the printer, the bind the texts as required). This information is presented first as an overview, then again in more detail in subsequent chapters, thereby offering a format that can be utilised by the reader in a number of ways. The book then moves on to discuss the use of advertisements and title pages as marketing tools – the economics of printing are constantly borne in mind. All the less familiar features that might appear on the page, apart from the actual text, such as printer’s devices (the fore-runner of the logo), marginal notes, signature marks and so on are explained in detail and the various ways of reproducing images, including movable diagrams which were popular in astronomy and navigation books, are all discussed and illustrated. By the end of Part 3, we have pretty good idea how an early printed book came into being. But for the researcher of course, this is just the beginning!

The remaining two parts of the book are concerned with what we can learn of a book from looking at (not necessarily reading) the early printed text. What are it’s physical features and how should we handle old books? Werner deals with working with both a physical book in our hands, as well as the increasing number of early printed texts which are now available in digital form. Clearly this advance in technology makes such texts far more accessible to us and possibly easier to navigate, but digitization brings it’s own problems. Although we can see all the words, we cannot feel the pages, smell the book, see the binding – and often, it is not at all certain whether or not we are looking at the complete book.

Werner ends by urging us to treasure and value these early books, not just for what is written within their pages, but what they can tell us about the world in which they were produced:

‘Books tell us stories. It’s easy enough to read what’s written. It’s harder to read in a different type of languge, to look at the signs left by long-ago workers about their unseen actions…. no book exists outside of it’s making’.

Dr Jill Francis, Library Assistant

Sarah Werner, Studying Early Printed Books (1450-1800): A Practical Guide (Wiley Blackwell, 2019) is available now on the New Acquisitions shelf in the newly reburbished library – come and have a look at both!

A timely reblog of a post on the archive of The School of Night, who treated our students to a wonderfully entertaining evening at the SI on 22 February. Impressive and inventive improvisation featuring Chaucer, Milton, Yeats, Beckett and of course, Shakespeare. The ‘new lost play’ found featured Venusian King Dobson and the reluctant stammering heir Prince Stanley – title suggestions for this new work welcome…

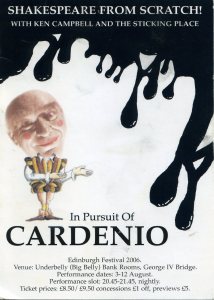

The Shakespeare Institute Library is delighted to be receiving the archive ofThe School of Night.Connected by name but not to be confused with Sir Walter Raleigh’s secret society, the improv company originated in a celebration of Shakespeare devised by the late, great Ken Campbell in 2005 forThe Globe.

This initial gift from the company to the SIL by actor Oliver Senton contains publicity material for many of the School’s performances including details of Ken Campbell’s In Pursuit of Cardenio, 2006 – a series of performances inspired by audience suggestions promising ‘Each night a new lost Shakespeare. Never seen before and never to be seen again!’

This initial gift from the company to the SIL by actor Oliver Senton contains publicity material for many of the School’s performances including details of Ken Campbell’s In Pursuit of Cardenio, 2006 – a series of performances inspired by audience suggestions promising ‘Each night a new lost Shakespeare. Never seen before and never to be seen again!’

As actors and audience mingled, a series of semi-spontaneous routines emerged through word suggestions and associations from the audience. Riffing in blank verse, iambic pentameter and sonnet form, Campbell’s troupe of actors improvised in Elizabethan style around possible scenes…

View original post 314 more words

Last year, the Royal Shakespeare Company held a grand jumble sale in Stratford-upon-Avon, offering about 10,000 unwanted stage properties. It was an imaginative way of funding the restoration of the theatre’s new costume department, A Stitch in Time, since patrons and theatregoers could actually buy a little piece of the Company, or of the actor who wore it, as their own personal souvenir. It was a roaring success and queues built up through the day for a chance to rake through the huge variety of uniforms, jewellery, shoes, hats and costumes used in former productions.

Last year, the Royal Shakespeare Company held a grand jumble sale in Stratford-upon-Avon, offering about 10,000 unwanted stage properties. It was an imaginative way of funding the restoration of the theatre’s new costume department, A Stitch in Time, since patrons and theatregoers could actually buy a little piece of the Company, or of the actor who wore it, as their own personal souvenir. It was a roaring success and queues built up through the day for a chance to rake through the huge variety of uniforms, jewellery, shoes, hats and costumes used in former productions.

We are used these days to seeing all manner of sophisticated and realistic stage properties in the theatre. Sets, lighting and stage effects may vary from the sparse to the elaborate, according to the vision of the director: the variety of styles stimulates and engages an audience, besides keeping theatre critics in work. The idea still persists, however, that Elizabethan theatre was very close to what might be called minimalist: a bare stage, no scenery, very basic props if any, and actors performing in the dress of the period. Some critics have claimed that the early stage was occupied predominantly by the playwright’s language. The simplicity of the Wooden ‘O’, empty of visual ornament, was thought to appeal mainly to the mind. So, people went to ‘hear’ a play rather than to ‘see’ it: it was something to be considered rationally rather than engaging all the senses. But, the Elizabethan theatre used more sophisticated props and stage effects than is often assumed.

That the early stage involved visual spectacle is borne out by the eye-witness accounts of contemporary theatre goers. The astrologer and herbalist Simon Forman, who was a member of Shakespeare’s circle, left a number of manuscripts, one of which – the ‘Book of Plaies’- records descriptions of the productions he saw between 1610-11. He comments with fascination on the action around Macbeth’s chair – a very solid and visible chair – in the banquet scene.

That the early stage involved visual spectacle is borne out by the eye-witness accounts of contemporary theatre goers. The astrologer and herbalist Simon Forman, who was a member of Shakespeare’s circle, left a number of manuscripts, one of which – the ‘Book of Plaies’- records descriptions of the productions he saw between 1610-11. He comments with fascination on the action around Macbeth’s chair – a very solid and visible chair – in the banquet scene.

‘the ghost of Banquo came in and sat down in his (Macbeth’s) chair behind him, and turning about to sit down again,(he) saw the ghost: which affronted him so that he fell into a great passion of fear and fury’

He also mentions the bracelet in Cymbeline, the chest or trunk in which Iachimo, and Autolycus’ ‘pedlar packe’ in The Winter’s Tale.

We are fortunate to have the so-called Peacham drawing, now in the library of the Marquess of Bath at Longleat. It appears to depict a scene from Titus Andronicus where vigorous gesturing and several props and costume give a vivid impression of Elizabethan acting.

That the public stage was known for the presence on-stage of a number of eye-catching objects, is attested by Philip Henslowe, the leading theatre proprietor and manager of The Admiral’s Men. Henslowe’s extensive 1598 inventory of the company’s props describes articles from the fairly functional ‘paire of rough gloves’, ‘one plain crown’ and ‘one snake’, to articles designed to impress and boggle the eye: a golden sceptre, one Hell’s mouth’ one ‘tree of golden apples,’ ‘the cloth of the sun and moon’ and – most impressive –‘the city of Rome.’

‘Props’ – theatrical slang for properties – first appeared in the Oxford English Dictionary of 1841 and so Shakespeare and his contemporaries would not have used the shortened word. Props include all the moveable, physical objects of the stage: costumes, furniture and stage hangings. But we have no record of the props used by Shakespeare’s Company. How did they create the Capulet family vault, into which Romeo breaks with ‘a torch, a mattock, and a crow of iron’ How too, were Caesar’s Rome, the Forest of Arden and The Tempest’s peacock-drawn flying chariot realised on stage?

Inevitably, Henry V comes to mind, where attention is drawn to the theatre’s inability to create a wholly realistic scene. ‘Can this cockpit hold/The vasty fields of France?’ asks the Chorus. And then comes the suggestion that the audience should employ its ‘imaginary forces’, and ‘piece out imperfections [with] its thoughts,’ so creating France and England for itself.

Shakespeare’s audience would have had no difficulty in understanding visual clues and metaphors. A cloak would signify outdoors, while riding boots a suggested a journey or a traveller. We see this in A Midsummer Night’s Dream where the Mechanicals use ‘lime and rough-cast’ to create a wall and a ‘lanthorn, dog and bush of thorn’ to represent the moon. There must, in order to portray Bottom’s ‘translation’ have been a comical ass’s head too.

Stage directions give us considerable information about props: ‘ Enter a messenger with two heads and a hand’ and ‘Enter the Clown with a basket, and two pigeons in it.’ Elsewhere, detailed and precise descriptions conjure up visual images. Shakespeare’s Company might well have had an object which signified Titania’s ‘mossy bank’ but it took Shakespeare’s words to dress it with flowers. Shakespeare himself must have responded strongly when he read – and virtually copied – Petrach’s description of Cleopatra’s barge. The image is multi-sensory: perfumed sails, flute music and a vessel so decked with gold that it ‘burns’, almost making the hearer blink.

Dress signified social status and the centuries-old Sumptuary laws forbade ordinary people to wear certain colours and costly fabric but theatre companies got round the difficulty by purchasing a licence from the monarch. For ordinary parts, players used their own clothes but Henslowe’s inventory lists clothes made in the silks, cloth-of-gold, satins and velvets reserved for gentry. These would be worn to play kings and nobles. Such costumes were often left to actors by fellow thespians, or high-ranking citizen bequeathed luxurious clothing to servants who in turn sold them on to theatre companies.

Stage hangings served as places of concealment for spying and hiding, as in the scene in Hamlet where Polonius is stabbed through the arras. Small spaces such as a cell, study or bedroom would be disclosed when hangings were drawn back; or a spectacular object hidden until the moment came for the Grand Reveal. The fabric of the theatre was a prop in itself: a trap door in the stage might be a grave, a pit, or the mouth of Hell, sometimes emitting smoke and fireworks. The upper gallery of the playhouse served as Juliet’s balcony or Cleopatra’s monument, or might become the wall of a city or a castle. Pillars supporting the canopy or roof set the scene for Greek temples or Roman palaces.

Other smaller props also played their part. Rings appear in no fewer than 15 plays of Shakespeare. They are often love-tokens and are given as symbols of binding emotional commitment and fidelity. Juliet sends a ring to Romeo to indicate her continuing love, despite the fact that he has killed her kinsman. But rings can often go astray; may be lost, stolen, sold or mistakenly given to the wrong person. Much confusion, either tragic or comic results. In an attempt to guide its audience through the vagaries of the plot and it is amusing to note that 2009 production of All’s Well had its actors wear rings with stones the size of golf balls which lit up in different colours.

We know that many Elizabethans kept skulls on their desks as a memento mori, in an age where violent death and epidemics of disease were a fact of life. Some critics believe Hamlet to be the first play in which a skull is used as a prop. The gravedigger’s scene allows both Hamlet and the audience to contemplate mortality, at first objectively, and then subjectively when the skull of Yorick is identified.

Severed heads and limbs, blood and gore, the plucking out of eyes and tongue….. There was a long way to go before Kensington Gore, the generic term for stage blood, achieved a convincing colour and viscosity in our own era. Shakespeare had to be satisfied with a bladder of pig’s blood to achieve his shock effects.

So much for a bare stage and the notion that plays were only to be heard. Shakespearean productions were fairly crowded with props – 572 at the last count. The images are embedded in our culture: the politics, skulduggery and drama surrounding coronets and crowns, Antigonus pursued by a bear, Desdemona’s handkerchief, swords, spears and foils, digging tools, paper as letters or maps, Ophelia’s herbs and Titania’s bower. Add to these, the music of trumpets, drums, viols and citterns and, occasionally, even the reek of cordite as Jupiter in The Tempest descended, astride an eagle, throwing thunderbolts. I call that a complete theatre experience.

Bettina Harris, Library Support Assistant