2015 has been designated a year of Anglo-Chinese cultural dialogue, and it has already seen the Royal Shakespeare Company, with a certain amount of help from the Shakespeare Institute, embarking on a project to produce a new, theatre-friendly translation of the Complete Works into Mandarin; April 2016, the month that sees the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, will see the RSC taking Gregory Doran’s productions of Richard II, Henry IV parts 1 and 2 and Henry V to Beijing and Shanghai; indeed the whole of next year will find the British Council co-ordinating Shakespeare-related events all over the world under the slogan ‘Shakespeare Lives.’ All in all, if a Shakespearean scholar with an interest in the work of the RSC can’t get flown to China by the British Council in 2015 or 2016, he or she should probably give up all hope of it ever happening.

I was one of the lucky ones, this year, invited to spend the last week before the autumn term touring China to give a series of what are called ‘Smart Talks’ – mildly evangelistic lectures about key aspects of British culture and education, in my case Shakespeare. I was delighted to accept, for a number of reasons. One is that I have cherished a side-interest in the intersections between Shakespeare and China ever since I was a PhD student working on early stage adaptations of the plays, when I first encountered the 1695 semi-opera The Fairy Queen – a version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, with wonderful music by Purcell, in which the play’s culminating marriages are adorned not by the mechanicals’ performance of ‘Pyramus and Thisbe’ but by the fairies summoning a spectacular vision of Chinese landscapes and culture, complete with silks, ceramics, and oranges. In the autumn of 1999, moreover, my wife Nicola Watson and I held visitorships at PKU – Peking University, an elite institution sufficiently conservative to have clung to the older English way of spelling the city’s name – and I have tried ever since to keep in touch with the faculty and students we met during that eye-opening and enriching encounter with the city and its intellectuals.

I was one of the lucky ones, this year, invited to spend the last week before the autumn term touring China to give a series of what are called ‘Smart Talks’ – mildly evangelistic lectures about key aspects of British culture and education, in my case Shakespeare. I was delighted to accept, for a number of reasons. One is that I have cherished a side-interest in the intersections between Shakespeare and China ever since I was a PhD student working on early stage adaptations of the plays, when I first encountered the 1695 semi-opera The Fairy Queen – a version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, with wonderful music by Purcell, in which the play’s culminating marriages are adorned not by the mechanicals’ performance of ‘Pyramus and Thisbe’ but by the fairies summoning a spectacular vision of Chinese landscapes and culture, complete with silks, ceramics, and oranges. In the autumn of 1999, moreover, my wife Nicola Watson and I held visitorships at PKU – Peking University, an elite institution sufficiently conservative to have clung to the older English way of spelling the city’s name – and I have tried ever since to keep in touch with the faculty and students we met during that eye-opening and enriching encounter with the city and its intellectuals.

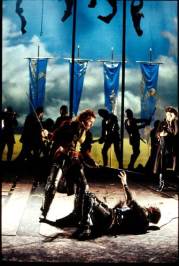

Coriolanus, Beijing People’s Arts Theatre, 2013

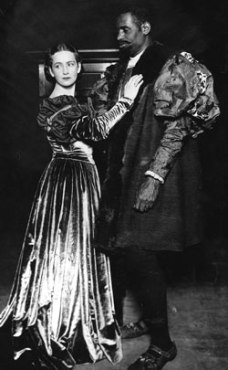

Since then, Chinese participation in the international Shakespearean theatre has become much more conspicuous. In 2013, for instance, the Beijing People’s Arts Theatre brought their production of Coriolanus to the Edinburgh Festival, an event for which I was commissioned to write a programme note, and I revisited their home city that autumn to teach a guest class on Othello at PKU — at a time when our best man, conveniently, held the post of British Ambassador to China, and thus had a very comfortable prime ministerial suite at his disposal on Guang Hua Lu. In collaboration with my Singapore-based colleague Li-Lan Yong, moreover, I am at present designing an online MA module about recent performances of Shakespeare in China, Japan and Korea, so I was more than happy to have the chance to get over there again.

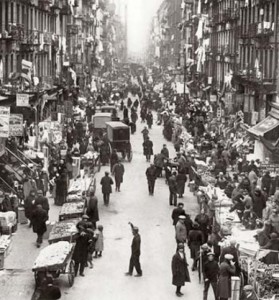

After contributing a short on-line interview to the British Council’s Voices website sketching some of the themes I would be exploring in my lectures – I reported for duty at the arrivals hall of Beijing airport on the morning of September 20th. In 1999 Nicky and I were among the last arrivals to pass through the small, battered, state-poster-adorned 1950s terminal which Mao and Nixon had known: today the airport buildings, connected by a swish internal rail system, are vast, sweeping, cosmopolitan spaces covered in the usual large shiny advertisements for international brands. In 1999, similarly, Nicky and I stayed at a wonderfully old-fashioned hotel opposite the PKU campus, the Changchungyuan, known as ‘The Intellectuals’ Hotel’, which provided only pot noodles and jasmine tea for sustenance, and which boasted a diagram of its fire escapes labelled in English as ‘Sketch of Urgent Scattered’: in 2015, my British Council organizer Fraser Deas had me driven to the Chaoyang Westin, an almost embarrassingly luxurious American chain hotel near the embassy district. Beijing’s polluted smog, however, turning the clear blue skies through which my flight had passed over Mongolia to a muffled not-exactly-grey, hadn’t changed at all – in fact my first lungfuls on stepping off the airliner, tinged with the same distinctive local n otes of coal, sulphur and charcoal, transported me at once to the city of my first arrival. That jetlagged Sunday afternoon and evening were about the only free time I had for a week, and I spent them with a former PKU student and her family, exploring Chaoyang Park and its fairground attractions, talking with the kite-flyers I was pleased to find still plying their hobby in commercialized, built-up, internationalized post-Olympics Beijing, watching the personal ads and patriotic videos projected on the immense TV screen in the roof of the Place shopping mall, and eating an exceptionally good meal.

otes of coal, sulphur and charcoal, transported me at once to the city of my first arrival. That jetlagged Sunday afternoon and evening were about the only free time I had for a week, and I spent them with a former PKU student and her family, exploring Chaoyang Park and its fairground attractions, talking with the kite-flyers I was pleased to find still plying their hobby in commercialized, built-up, internationalized post-Olympics Beijing, watching the personal ads and patriotic videos projected on the immense TV screen in the roof of the Place shopping mall, and eating an exceptionally good meal.

Chinese internet company Net Ease

The Monday offered a more representative glimpse of how the rest of the week would be: in the morning, a drive to the familiar Haidian district, near PKU, to record a video interview for the huge Chinese internet company Net Ease; around lunchtime, a press conference at the hotel, conducted, via a translator, with the Beijing Evening News and representatives of three other local media organizations (as curious about the current state of British education as about Shakespeare); in the afternoon, a drive to Beijing Middle School Number 4 to give a Smart Talk to a packed hall of 14-17 year-olds; and in the evening, a return to PKU to give a paper on Hamlet to Zheng Xiaochang’s Shakespeare seminar group, including PKU graduate and former Institute visiting scholar Jia Xu.

I had long ago heard of Beijing Middle School Number 4, the most academically fierce secondary school in the capital, which according to its proud headmistress Chang Jing sends 100 of its 1400 students to PKU every year, and it did not disappoint: its architectural core is two former French Jesuit secondary school buildings just over the wall from Beihai Park, on the site of what was once the elite training facility of the Imperial Guard, and its ethos retains something of the place’s dual past. In the playground – or rather, exercise area — squads of goose-stepping students were competing to be chosen to take the salute during an impending sports day. As a prologue to my lecture, a fifteen-year-old male student performed Macduff’s speech on learning that his family have been murdered and a fifteen-year-old female student performed Lady Macbeth’s first speech, both of them fearlessly, with absolute commitment, and in near-flawless English.

As the British Council had requested, I rewarded the posers and answerers of questions with small trinkets selected from the gift shops of the RSC and the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, in particular pin-on badges displaying short quotations from the plays. At that school I particularly gave out some which bear a phrase from The Tempest, ‘Thought is free’: may their wearers bear it out.

My audience in the evening at PKU were as well-informed and acute as always, but then that is a university which has a reputation for Shakespeare studies going back to the early days of Mandarin translation in the 1900s, and its English literature faculty never forget that in the late 1930s and 1940s it was the workplace of the great Cambridge-educated poet and critic William Empson. (When the Japanese invasion forced the university to abandon its campus and its library and try to teach what it still could in retreat, Empson is said to have typed the whole text of Othello from memory – though the typescript no longer survives to be checked for completeness). Zheng Xiaochang, Jia, one of the RSC’s translation team and I had dinner together in the seminar room itself after the session was over – possibly the best Chinese takeaway I have ever eaten.

Tuesday found Fraser, his colleague Diana and I flying down to the ancient rival of Beijing (‘northern capital’), namely Nanjing (‘southern capital’). Equally steamy and dirty in its atmosphere, and in the business district where we stayed overnight just as generically built-up (this time the skyscraper hotel was a Sheraton), Nanjing’s streets otherwise reminded me less of today’s Beijing than of the one I remembered from 1999, with fewer signs transliterated in pinyin and more bicycles and freight-bearing tricycles holding their own among the encroaching cars. Miles of medieval city wall survive, and there is a Forbidden-City-like palace complex fronting a famously beautiful lake, and temples and pagodas adorn the surrounding mountains, but we were destined to see none of this (nor did I so much as glimpse the Yangtse, save from the incoming ‘plane) – instead we were driven out to Nanjing University’s elegant, tree-planted new out-of-town campus some distance from the city centre. More diplomatic small-talk with deans and faculty; ritual exchanges of gifts; another superb meal (as always, our Chinese hosts were surprised by the visiting Britons’ ability to eat with chopsticks – the existence of a vast worldwide culinary diaspora seems to remain a secret in China itself); and a packed lecture hall of lively undergraduates and faculty to hear my Smart Talk. (These included, incidentally, the promising Shakespeare critic Xing Chen, recently back from Edinburgh, who presented me with a copy of her new book Reconsidering Shakespeare’s Lateness for the Institute library). I managed a swim in the hotel pool before getting to bed, but it’s not the same thing as a classical Chinese lake.

Wednesday: southwards once more, to Guangzhou. Given that Birmingham has an office in Guangzhou I was particularly curious to see the city formerly known as Canton, though my expectations weren’t high – the reports I had heard spoke of an overdeveloped, shapeless industrial conurbation which has supposedly sold its soul to international capitalism. In the event I was pleasantly surprised by a city which, though some of its downtown areas offer as arid an assembly of generic luxury shopping malls as does the Orchard Road district of Singapore (of which the lush vegetation and ubiquitous bougainvillea continually reminded me), has a real swagger and distinctiveness to its  recent architecture (its skyscrapers somehow add up to a harmonious and imposing skyline, in a way which Beijing’s miscellaneous gigantisms never do) , and which retains a definitely and enjoyably southern atmosphere throughout. In what remained of the afternoon once we had checked into another immense corporate hotel, I took a cab to the silk market, and as the sudden tropical darkness fell I dined in the open air beside the Pearl River (on a local speciality, a superb hot and sour frog soup) before finishing the day with a viewing of the spectacularly-lit skyscrapers from a boat. The Canton Tower – a structure that resembles a giant tulip vase woven in a basketwork of glass and steel – is especially striking: lit in ever-changing combinations of blue and orange and red, it is quite beautiful enough to serve as a modern cathedral or as a monument to art itself, but around its summit all its revolving neon display is currently proclaiming is a series of advertisements, notably for Pantene shampoo.

recent architecture (its skyscrapers somehow add up to a harmonious and imposing skyline, in a way which Beijing’s miscellaneous gigantisms never do) , and which retains a definitely and enjoyably southern atmosphere throughout. In what remained of the afternoon once we had checked into another immense corporate hotel, I took a cab to the silk market, and as the sudden tropical darkness fell I dined in the open air beside the Pearl River (on a local speciality, a superb hot and sour frog soup) before finishing the day with a viewing of the spectacularly-lit skyscrapers from a boat. The Canton Tower – a structure that resembles a giant tulip vase woven in a basketwork of glass and steel – is especially striking: lit in ever-changing combinations of blue and orange and red, it is quite beautiful enough to serve as a modern cathedral or as a monument to art itself, but around its summit all its revolving neon display is currently proclaiming is a series of advertisements, notably for Pantene shampoo.

On Thursday Fraser took me to the British Council’s Guangzhou offices to give another press conference (during which I waxed as lyrical as ever about the life-enhancing charms of Stratford and Edgbaston), and we than had lunch at a nearby restaurant, the menu chosen by the Council’s local driver. I passed the initial test of eating chicken feet with chopsticks (they were excellent), and all relaxed, and we were then told at great length about how the Cantonese way of preparing goose is self-evidently preferable to any possible recipe for Peking duck. After that, it was time to head out to Guangdong Foreign Studies University for the last of my lectures – this one prefaced by a formal session of diplomatic small-talk with the head of the university, in a magnificent reception room adorned with paintings and draperies.

One reason for this particularly marked welcome (at a university, founded by decree of Zhou En Lai, which trains future diplomats and others in over 20 different languages, a sort of Chinese counterpart to SOAS) was the presence of Duncan Lees, a distance learning student of the Shakespeare Institute who is an assistant professor at GFSU and a conspicuously inventive teacher of Shakespeare. In the few minutes that remained before I was due on stage Duncan showed me the university’s cherished statue of Shakespeare. It stands on the edge of jungle, among a canon of other state-approved artistic and philosophical worthies: Marx, Tolstoy, Confucius, Lu Xun, Beethoven – an intriguing counterpart to the more familiar pantheon of colleagues who flank Shakespeare above the main door of the Aston Webb building.

My horoscope in the China Daily that morning urged me to ‘undertake travel, and attend cultural events, for the more your own mind is enriched the more you will have to share with others,’ so though frustrated in my desire to see some Cantonese opera while in Guangzhou (apparently it mainly happens in the afternoons, when I wasn’t free) I happily accepted Fraser’s suggestion that he should put his fluency in at least Mandarin if not Cantonese at my disposal on an excursion to anything historical or cultural which I might fancy that night. I chose the Liurong Temple, with its celebrated Pagoda of the Six Banyans (1097), near which a taxi duly deposited us well after dark. The intricate surrounding streets and alleyways looked suspiciously like the venues for confrontations with gangs of pirates in a martial arts movie, but fortunately the locals we met during our protracted wanderings in search of the well-screened monument (especially a tailor, who drew an elaborate map) were universally friendly (unless you count the large rat we encountered near a fruit stall). When we finally found the temple gates they had been closed to the public for hours, but despite a disapproving Buddhist monk making a mobile-phone call in the background Fraser managed to persuade a guard to let us far enough inside at least to see the dim pagoda looming through the darkness between its sacred trees. Local culture that evening otherwise consisted of another excellent fish restaurant by the river.

I parted from the British Council on Friday morning at Guangzhou’s main railway station, and went through the surprisingly elaborate border procedures which nearly twenty years on from the 1997 handover are still required for anyone passing from the rest of China into Hong Kong.

Indeed, on arriving at Kowloon three hours to the south I not only had to deposit my suitcase in left luggage, but had to change my remaining Chinese yuan into Hong Kong dollars (discovering in the process, incidentally, that one of my 100 yuan notes, worth about £10, was a forgery, symptom of an increasingly widespread problem in the Chinese economy). I had an engagement to give a PhD supervision in the early evening to Miriam Lau, a split-site Shakespeare Institute student who works at Hong Kong Polytechnic University and is writing a thesis about Shakespearean performance in Hong Kong and its cultural valences since 1997, but I did manage take the Star Ferry across the harbour and the sometimes near-vertical Peak Tram to the island’s summit to admire  the view before returning to Kowloon to see Miriam.

the view before returning to Kowloon to see Miriam.

After our supervision there was just time for her to show me the arcade of wedding-accessory stalls she had patronized while making the preparations for her wedding last year (an event which for her had involved at least 3 entire outfits), and to share some street food as the garish neon lights lit up around us, before I took a cab to the airport to catch the 11.05pm British Airways flight back to London.

One last minor observation. Hours after my arrival home, it would be simultaneously the first day of term, my birthday, and the Chinese mid-autumn moon festival, so in order to mark this convergence – and a lunar eclipse to boot – I took a great deal of advice and stocked up, before my departure, on what I was assured were the best moon-cakes Hong Kong could provide. These are from the Kee Wah bakery, but they weren’t the brand I had seen advertised most conspicuously during the week, from Beijing through Nanjing and Guangzhou right down to Hong Kong itself. When Nicky and I first visited Beijing, in 1999, seven years after we had first tasted what was then a local brand of coffee during a visit to some friends in Seattle, the city had just seen the opening of China’s first branch of Starbucks. In 2015 the country which when I was growing up was filling TV new s bulletins with images of the Cultural Revolution, and which is still a one-party communist state committed to a militantly secular materialism, is full of branches of a capitalist coffee-shop chain, all of them offering to adorn the ancient religious festival of the autumn moon with Starbucks’ own-brand moon-cakes.

s bulletins with images of the Cultural Revolution, and which is still a one-party communist state committed to a militantly secular materialism, is full of branches of a capitalist coffee-shop chain, all of them offering to adorn the ancient religious festival of the autumn moon with Starbucks’ own-brand moon-cakes.

Present-day China is palpably hungry for the jewel in the British Council’s crown, Shakespeare – international, exotically western in origin, but adaptable to local theatrical and cultural preferences – but its audiences seem to want American coffee in their theatre foyers too.

Prof. Michael Dobson, Director of the Shakespeare Institute

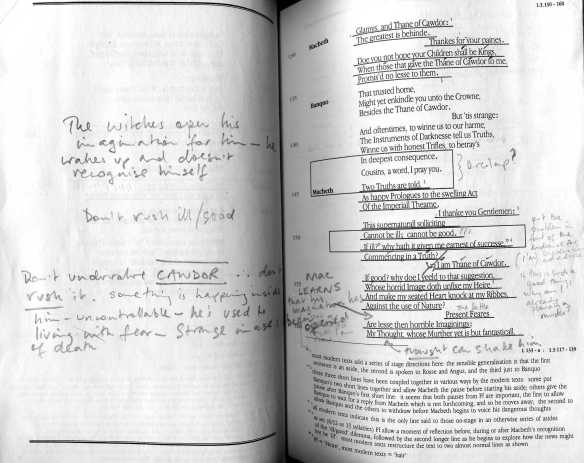

Whilst working on Hamlet, West produced three notebooks and one very heavily annotated script. The notebooks cover his initial thoughts and ‘homework’ on the play; his rehearsal process; and fine-tuning of his performance in previews. Evidently a cerebral actor, West’s rehearsal notebook goes into great detail on Hamlet’s relationships with other characters as well as discussing major themes in the play. His ‘reading list’ includes sources as diverse as The Spanish Tragedy, Festen, Fight Club and Batman.

Whilst working on Hamlet, West produced three notebooks and one very heavily annotated script. The notebooks cover his initial thoughts and ‘homework’ on the play; his rehearsal process; and fine-tuning of his performance in previews. Evidently a cerebral actor, West’s rehearsal notebook goes into great detail on Hamlet’s relationships with other characters as well as discussing major themes in the play. His ‘reading list’ includes sources as diverse as The Spanish Tragedy, Festen, Fight Club and Batman.

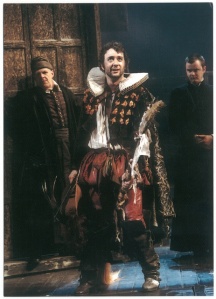

In 2016, as part of the birthday celebrations also marking 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, Samuel West, as Garrick, narrated the actor-manager-playwright’s 1769 Jubilee Ode at Holy Trinity Church giving it its first full-scale performance since the eighteenth century.

In 2016, as part of the birthday celebrations also marking 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, Samuel West, as Garrick, narrated the actor-manager-playwright’s 1769 Jubilee Ode at Holy Trinity Church giving it its first full-scale performance since the eighteenth century.

However, the most famous natural landmark is the Fairy Ring – a dark, circular patch of long grass. The fairies present in fairy rings could not be seen unless you stood in the middle of their circle dance. Alfred Nutt, alluding to the fairy dance by moonlight, describes it as “the classic manifestation of the fairy folk… in wild and desert places.” He thought that it had a realistic basis in the superstition that “night is essentially the time for growth” and that the ritual which sought to evoke growth was “frenzied and orgiastic.” Fairy dancing was associated with the idea that saltation assists the growth of the corps. Violent action has a magical and sympathetic effect upon the powers of nature, and the emanations of action strengthen the supernaturals in their task and are passed on to them; or, by sympathetic magic, they encourage them to similar exertions. Many primitive dances assume the form of imitative motions pantomimic of the growth of the crops, or of vegetation. Participants forming a circle and dancing with their backs to the centre.

However, the most famous natural landmark is the Fairy Ring – a dark, circular patch of long grass. The fairies present in fairy rings could not be seen unless you stood in the middle of their circle dance. Alfred Nutt, alluding to the fairy dance by moonlight, describes it as “the classic manifestation of the fairy folk… in wild and desert places.” He thought that it had a realistic basis in the superstition that “night is essentially the time for growth” and that the ritual which sought to evoke growth was “frenzied and orgiastic.” Fairy dancing was associated with the idea that saltation assists the growth of the corps. Violent action has a magical and sympathetic effect upon the powers of nature, and the emanations of action strengthen the supernaturals in their task and are passed on to them; or, by sympathetic magic, they encourage them to similar exertions. Many primitive dances assume the form of imitative motions pantomimic of the growth of the crops, or of vegetation. Participants forming a circle and dancing with their backs to the centre.