‘Dare, always dare’ wrote Lilian Baylis, that great stalwart of the Old Vic. Her words must be the most fitting motto for the world-renowned theatre whose Bicentenary falls this month. A special season to celebrate its landmark anniversary includes a new Dickens adaptation, an Ayckbourn play, a new musical dance production, a Birthday street party and Open House, marching bands and various community activities.

Yet the survival of the Old Vic for over two centuries is little short of miraculous: if its spirit is daring, its continued existence has always been precarious in the extreme. It has borne a variety of names – The Royal Coburg Theatre, Royal Victoria Theatre, New Victoria Palace, Royal Victoria Hall and Coffee Tavern. It has been sold and resold, refurbished, gutted and refurbished again. Neglected, bombed and fallen into disrepair, it has even been threatened with demolition. At the outset, it was built on the dubious wasteland of the Lambeth marshes. Managements, transient and money-grubbing, or else comprising those passionately committed figures who have made the Old Vic their life, have come and gone. It has been notorious for drunken, low-life audiences and then, in total contrast, become a temperance hall. It was claimed as the London home of Shakespeare and was the proving ground for many of our greatest actors. The National Theatre had its beginnings there and an adult education college grew up on its premises. And throughout its long history, the Old Vic has lurched through financial hardship and disaster, beset by that traditional curse of all theatres: money, money, money.

The theatre – The Coburg –was built near to the grand new Waterloo Bridge. There were immediate difficulties with money, the projected cost of £4,000 becoming £12,000. The Waterloo Bridge Company, aware of the tolls it could collect from large audiences crossing the river, stepped in with funds. At last, in May 1818, the theatre opened offering melodrama and pantomime. The season was a success and the house underwent its first ever re-embellishment, showing off the famous, five tons looking-glass curtain. This comprised sixty-three mirrors in a gilt frame, which reflected the audience, but was so heavy that it damaged the roof and eventually had to be removed.

The theatre – The Coburg –was built near to the grand new Waterloo Bridge. There were immediate difficulties with money, the projected cost of £4,000 becoming £12,000. The Waterloo Bridge Company, aware of the tolls it could collect from large audiences crossing the river, stepped in with funds. At last, in May 1818, the theatre opened offering melodrama and pantomime. The season was a success and the house underwent its first ever re-embellishment, showing off the famous, five tons looking-glass curtain. This comprised sixty-three mirrors in a gilt frame, which reflected the audience, but was so heavy that it damaged the roof and eventually had to be removed.

The Coburg went on to offer spectacular productions: an enormous ship ploughed through Arctic ice, while an Indian piece featured slaves, a real elephant, music and cannon fire. By 1824 a new impresario, George Davidge, had taken over the lease and the first attempts at Shakespeare – of a sort – were put on. As a minor theatre, The Coburg was constrained by ancient royal licences which forbade presentation of Shakespeare or any straight play. To get round the law, a melodrama of Richard III was presented, which contained various musical interludes and which, to the chagrin of several actors hoping for a juicy part, starred a real horse called ‘White Surrey.’ Davidge pushed his luck further with the Three Caskets – an adapted Merchant of Venice – while Lear became The King and His Three Daughters. But in a bold coup the great and outrageous  Shakespearean actor, Edmund Kean was engaged to play Richard III, Lear and Othello over six nights. Kean’s appearance on June 27th 1831 is legendary, for this was the occasion on which, fancying that Iago had received greater applause than himself, he railed at the audience, calling them ‘a set of ignorant, unmitigated brutes.’ Davidge had to appear before a Commons Select Committee to explain his flouting of the law. He got away with it: Shakespeare was to be preferred to the doggerel of melodrama. But again, money ran out, and the lease was sold.

Shakespearean actor, Edmund Kean was engaged to play Richard III, Lear and Othello over six nights. Kean’s appearance on June 27th 1831 is legendary, for this was the occasion on which, fancying that Iago had received greater applause than himself, he railed at the audience, calling them ‘a set of ignorant, unmitigated brutes.’ Davidge had to appear before a Commons Select Committee to explain his flouting of the law. He got away with it: Shakespeare was to be preferred to the doggerel of melodrama. But again, money ran out, and the lease was sold.

The new owners redecorated the auditorium, built a new stage and re-named the theatre. But the entertainment at The Royal Victoria became even rougher and more raucous. It became known as the most notorious drinking den in town, where low-life patrons packed in, 3.000 at a time. Both Charles Dickens and Charles Kingsley wrote of audiences teeming with all ‘the beggary and rascality of London…from…neighbouring gin palaces and thieves’ cellars.’ A false alarm in 1858 caused a panicked stampede from the theatre in which people were killed or badly trampled. There had been no outbreak of fire but the incident did nothing to rescue the Victoria’s reputation.

By 1870, the Victoria had become badly in need of repair. Sold to a limited company, it was marked for demolition. A new splendid theatre was to be created. But money again dictated events and the New Victoria Palace was built between the original side-walls and the original roof. But, while still The Palace, the theatre did not thrive and was put up for auction twice more in the 1870s.

A remarkable metamorphosis was at hand when a Company devoted to temperance took out the lease. A music and dancing licence was secured for what now became The Royal  Victoria Hall and Coffee Tavern. A tavern it most certainly was not, for no alcoholic drink was served at the bar for the next fifty years. Under the Company secretary, Emma Cons, variety acts innocent of innuendo, indecency or vulgarity were put on. Their purpose was the moral improvement of the lower orders. Supported by the Archbishop of Canterbury himself, and employing a clergyman as stage-manager who monitored the modestly-proper length of the lady performers’ skirts, the Royal Victoria was praised in the Birmingham Daily Post for its ‘civilisation of the roughs’ and for creating an ‘atmosphere of purity and truth which must cause rejoicing in Heaven.’

Victoria Hall and Coffee Tavern. A tavern it most certainly was not, for no alcoholic drink was served at the bar for the next fifty years. Under the Company secretary, Emma Cons, variety acts innocent of innuendo, indecency or vulgarity were put on. Their purpose was the moral improvement of the lower orders. Supported by the Archbishop of Canterbury himself, and employing a clergyman as stage-manager who monitored the modestly-proper length of the lady performers’ skirts, the Royal Victoria was praised in the Birmingham Daily Post for its ‘civilisation of the roughs’ and for creating an ‘atmosphere of purity and truth which must cause rejoicing in Heaven.’

And then Lilian Baylis was invited to join the Victoria. She was a niece of Miss Cons and had had a remarkable early life touring South Africa with her parents’ concert party. She was a woman of parts: could sing, play various instruments and had taught dancing and music. She began work at the age of 24 and earned £1 a week, gradually assuming more managerial duties and taking over the lease on the death of her Aunt in 1912.

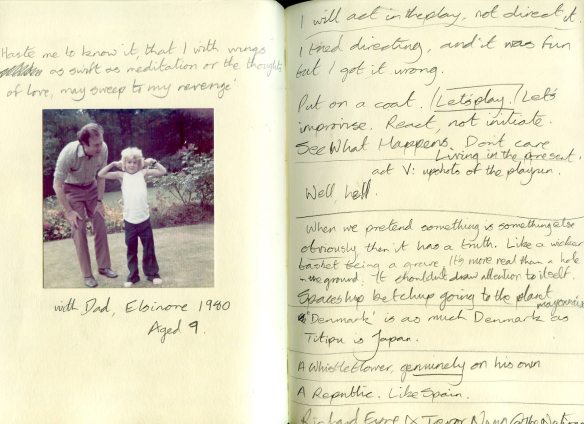

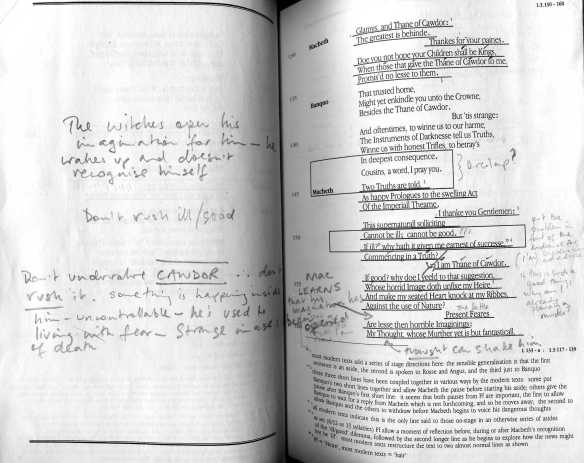

Miss Baylis’ real love was opera; she had already staged The Bohemian Girl, but one night a male voice spoke to her as she lay in bed. She had quite often had nocturnal dialogues with Jesus but this voice instructed her to produce his plays. It was Shakespeare’s. We know, of course, what great days were to come and how the arrival of the actor-manager Ben Greet was viewed as a further Act of God by Miss Baylis. Under Greet, the Old Vic Shakespeare Company was formed and performed the entire First Folio over the course of seven years. Hamlet was given in its entirety, a stint of five hours, and became an Old Vic tradition. The theatre could now properly be called that after Miss Baylis formally adopted the popular local nickname as its official title.

a male voice spoke to her as she lay in bed. She had quite often had nocturnal dialogues with Jesus but this voice instructed her to produce his plays. It was Shakespeare’s. We know, of course, what great days were to come and how the arrival of the actor-manager Ben Greet was viewed as a further Act of God by Miss Baylis. Under Greet, the Old Vic Shakespeare Company was formed and performed the entire First Folio over the course of seven years. Hamlet was given in its entirety, a stint of five hours, and became an Old Vic tradition. The theatre could now properly be called that after Miss Baylis formally adopted the popular local nickname as its official title.

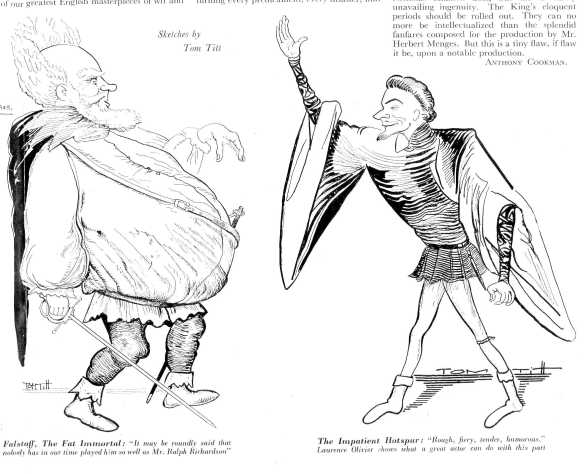

The Old Vic offered both classical drama and opera at moderate prices which meant that performers’ pay was low. When asked for a rise, Miss Baylis would reply, ‘Sorry, dear, God says no.’ But she had the knack of attracting talented young actors who then had the chance of playing a wide range of great Shakespearean roles. ‘God send me a good actor, and send him cheap’ was another classic Baylis saying. And God evidently obliged with the provision of some of our finest twentieth-century actors: Sybil Thorndike, Edith Evans, John Gielgud, Ralph Richardson, Peggy Ashcroft….. These were among the greatest years of the Old Vic. When Miss Baylis died in 1937 she had secured Michael Redgrave, Alec Guinness and Laurence Olivier. At least one of them would have a marked effect on the future of theatre in Britain.

The Old Vic was bombed during the Blitz and restored in the 1950s. Again the money gremlins struck and a budget of £30, 636 had risen to £75,000 by the time the works were finished in 1957. By 1961 the idea of a National Theatre situated on the South Bank had been revived, and Olivier was asked to be its Director. But not yet: in the meantime, the new N.T. was to be housed in The Old Vic. Yet another rather unsatisfactory refurbishment took place but it was not until 1976 that the N.T. eventually moved to its new home. ‘It is the chief labour of my life’ said Olivier.

The closing night remembered Lilian Baylis in Tribute to the Lady, with Peggy Ashcroft repeating the Lady’s threat to come back and haunt them all should her work, or the theatre itself, ever be put at risk. The Old Vic changed hands again in 1982 and was restored by the Canadian entrepreneur ’Honest Ed’ Mirvish to the tune of £2.5 million – before being put on the market yet again. Plans to make it a pub, bingo hall or lap-dancing club caused wide outrage and protest. The ghost of Miss Baylis undoubtedly played its part.

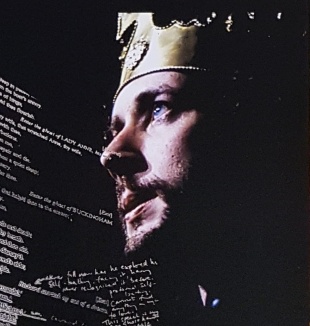

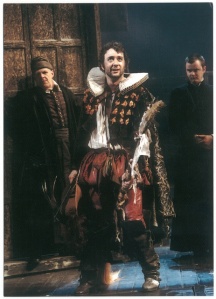

The Old Vic Theatre Trust 2000 acquired the building in 1998 and in 2003 Kevin Spacey was appointed Artistic Director. In his time there, Spacey mounted a series of screen projects, played Richard 11 and Richard III and numerous other parts. No other actor-director has received such consistent publicity as he did; the glamour of Hollywood clung to him and informed everything he attempted. ‘He’s done an incredible job’ was one comment when Spacey stepped down, ‘He’s totally revitalised the place.’

The present Artistic Director, Matthew Warchus, has a new vision for the Old Vic. A fuller programme comprises world premieres, revivals, dance, musicals and variety shows which build on the preceding 200 years of creative endeavour. ‘We hope to be a surprising, unpredictable, ground-breaking, rule-breaking, independent beacon of accessible, uplifting and unintimidating art.’ Is his new mission statement.

Happy Birthday, Old Vic.

Bettina Harris, Library Support Assistant